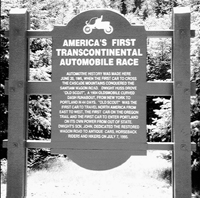

America's First Transcontinental Automobile Race

On June 23, 1909, a Ford automobile arrives in Seattle from New York City in 23 days flat, completing the first transcontinental automobile race across North America. This Model T Ford arrives first but is disqualified because the drivers changed the engine during the race. The winner (the second to arrive) is a Shawmut. The race is part of Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition (A-Y-P).

Initially as many as 35 autos were going to enter the race, but when the race started in New York City at on June 1, 1909 at 3:00 p.m., the exact moment that President Taft officially opened the AYP, only six vehicles crossed the start line. They were an Itala, Shawmut, Acme, Stearns, and two Model T Fords.

Sixty years after the first great columns of prairie schooners lumbered along the Oregon Trail, two tiny and primitive automobiles followed the historic ruts across the West. The year was 1905, and the cars were in the first transcontinental automobile race.

The pair of 7-horsepower Curved Dash (so called because of the sleighlike front of the body) Olds Runabouts made their historic journey from New York City to Portland, Ore. Essentially motorized buckboards, these were the first automobiles negotiating the Oregon Trail, first to cross the United States from east to west and the first over the Cascade Range. Although parts of the United States were quite "civilized," in 1905, the 20th century was only a spotty veneer over the western United States. The little cars and their drivers faced bad weather, sickness, wild animals, thirst, accidents and unforeseen breakdowns. Crossing the Oregon Trail was still a rough trip.

The pair of 7-horsepower Curved Dash (so called because of the sleighlike front of the body) Olds Runabouts made their historic journey from New York City to Portland, Ore. Essentially motorized buckboards, these were the first automobiles negotiating the Oregon Trail, first to cross the United States from east to west and the first over the Cascade Range. Although parts of the United States were quite "civilized," in 1905, the 20th century was only a spotty veneer over the western United States. The little cars and their drivers faced bad weather, sickness, wild animals, thirst, accidents and unforeseen breakdowns. Crossing the Oregon Trail was still a rough trip.

The automobile was a growing presence in larger cities and even in some towns. Endurance races and tours were popular events. The densely settled Eastern states had a network of established roads, some of which even had graveled surfaces, but most were little more than smoothed-out trails. There were less than 150 miles of hard-surface roads in the entire country, all of it in cities.

The race was a publicity event as well as a contest. The first prize was a very respectable (particularly in those days) one thousand dollars. James W. Abbott, a major organizer of the race, wrote: "[The] important purpose was to bring vividly to public attention a clearer knowledge about all phases of existing transcontinental highways."

Abbott worked for the Department of Public Roads in the Department of Agriculture. Together with Olds Motor Works and a group called The National Good Roads Association (a group of bicyclists who acted as the first highway lobby), he published an advertisement for entrants in the race, called "From Hell Gate to Portland." The Association's 5th annual convention was to be held at the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland on June 21, 1905.

The race began auspiciously in New York City on May 8, with fanfare and good weather. One of the cars, Old Scout was even cautioned for speeding. Everyone was optimistic. But, like so many earlier westbound emigrants, these pioneers found the trip much harder than expected. Organizers had estimated the trip would take 30 days. They were wrong.

The cars were single-cylinder, tiller-steered, chain-driven and water-cooled. Old Scout was driven by Dwight Russ, an employee of Olds and an accomplished driver. His mechanic and co-driver was Milford Wigle, also of Detroit. The other Runabout, Old Steady, was driven by Percy Megargel and Barton Stanchfield. Both Megargel and Huss had driven in tours and races. Huss had raced also in England and Europe, accumulating an impressive record of victories. Only 13 years after the first American car-the Duryea-was built, Americans were racing at home and abroad.

The previous year, a 90-pound "motor-bicycle" had crossed the continent from west to east, following (and often riding on) the tracks of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads. But driving a race over the Oregon Trail turned out to be a much greater challenge than riding a motorized bicycle.

For the race's organizers, a snow-free crossing of the Cascades was considered the most important factor. They had not considered the unpredictability of spring weather. Three days into the trip, rain began and continued for half of the race. It rained every day for three weeks. Miles and miles of the route became lakes and swamps. Dwight Huss wrote of following roads that were completely under water, and he steered by keeping parallel to the telegraph poles.

Because of supply logistics, the route followed the Oregon Trail as the Union Pacific followed the trail. Ruts from iron-tired wagons were the nearest things to interstate highways. At Julesburg, Colo., the cars turned northwest into Wyoming. They reached Cheyenne 11 days behind schedule.

Old Scout took an early lead and held onto it. The two Runabouts began meeting numerous covered wagons still using the trail. As one participant wrote: "We passed many parties of traveling prairie schooners to and from the east. These schooners, usually a single wagon drawn by two or four horses, or mules, with one or two saddle ponies and a cow tied behind, are visible for miles, their big white canvas bow tops glistening in the sunshine, and we often pass as many as half a dozen of them traveling together."

The race was a well-publicized and popular event for the lonely settlers. Townspeople, ranchers, cowboys and sodbusters rode for miles to see the Runabouts pass through their country. People were interested not in the sport of the race, however, but in the utility value of the machines. They wanted to know if automobiles were practical in the rugged West. Horses bucked and kicked as the cars chugged by. The riders laughed and stayed on their bucking mounts. They shouted at the drivers, "Good luck boys, give 'em hell!"

The race was a well-publicized and popular event for the lonely settlers. Townspeople, ranchers, cowboys and sodbusters rode for miles to see the Runabouts pass through their country. People were interested not in the sport of the race, however, but in the utility value of the machines. They wanted to know if automobiles were practical in the rugged West. Horses bucked and kicked as the cars chugged by. The riders laughed and stayed on their bucking mounts. They shouted at the drivers, "Good luck boys, give 'em hell!"

The drivers didn't give" 'em hell"-they got it. Navigating through the gumbo, Huss wrote, the cars carried a half-ton of mud. That nearly doubled the little cars' weights. (A popular joke of the time claimed that the cars sold for a dollar a pound-650 pounds for $650.) Two hundred pounds of tools and fuel were carried as well. The cars were packed to double their weight, counting the mud. Driver and mechanic added another three hundred pounds-7 hp to move nearly a ton. Surprisingly, on good stretches, the cars could actually speed along at 15 miles an hour!

There weren't a lot of good stretches, however. Huss wrote of one day in Wyoming, "we drove 18 hours, forded five streams and made a total of 11 miles."

Where the trail had dried, the ruts were so deep and numerous the cars couldn't stay out of them. Their axles high-centered between the ruts, forcing the drivers to dig out with shovels. They often had to back up half a mile to a place where they could steer onto relatively smooth ground. But soon, Huss said, they would end up high-centered once again. Iron-hard clay cut the tires to shreds. Rocky stretches were worse. One set of tires was worn out every 90 miles. Huss said he had no idea how many tires were destroyed on the trip.

Supplies, for the most part, were not a problem. Abbott arranged supply depots along the course. While gasoline was generally available, at least in small quantities (in drug stores, for dry cleaning), larger amounts had been stockpiled in advance by train and stagecoach. Stocks of oil, tires and batteries had also been arranged. The cars did not have magnetos. Instead, the engine spark was produced by dry-cell batteries, with a limited lifespan. Deep water would short out the batteries and the engines would die.